Five Key Takeaways from “Nuke Fest” 2019

This week, the nuclear policy community gathered in Washington, D.C. for the 2019 Carnegie International Nuclear Policy Conference, a biannual event that brings together participants from all over the world. A lot has changed in two short years; the suspension of the INF treaty, the inconclusive ending of the Hanoi summit, and the recent hostilities in South Asia, among other things, have created profound uncertainty about the future of arms control and disarmament. Nevertheless, there’s plenty that the panelists, commenters, and conference attendees seemed to (mostly) agree on. Here are five key takeaways:

1. The policy community remains far removed from the current U.S. administration on many issues. Appearances by U.S. Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Affairs Andrea Thompson and Special Representative for North Korea Steve Biegun gave participants the chance to ask hard questions about the Trump administration’s approach to arms-control negotiations.Biegun was adamant that the U.S. would offer no concessions, and that North Korea must move toward ending its nuclear program before receiving sanctions relief. “We are not going to do denuclearization incrementally,” he stated unequivocally during his panel. The responses from the audience, and the discussions that followed, showed that many recent decisions by the administration remain deeply unpopular.

2. Women are the future of nuclear policy. From the Young Professionals events that bookended the conference program, to moderator and New York Times Pentagon correspondent Helene Cooper only taking questions from women, to the side events dedicated to creating space for women and people of color, it was clear that the demographics of the nuclear policy world are shifting–and with them, the long history of male-dominated policy discussions and aggressively gendered language.

3. The U.S.-Russia relationship remains central to the international nuclear order, and it’s in trouble. Both days closed with fascinating panels focusing on the U.S. and Russia: the first featured Russia’s ambassador to the U.S., Anatoly Antonov, and the second, Igor Ivanov, former Foreign Minister and Secretary of the Security Council of Russia. Since the U.S. Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty withdrawal announcement, the future of the New START Treaty — the last restraint on Russian and U.S. nuclear arsenals — has taken center stage for policy-minded Russia watchers.As was frequently mentioned, a new U.S. presidential administration would have mere weeks to complete negotiations to extend the New START treaty past it’s February 5, 2021 expiration. Ambassador Antonov said that Russia would reject a last-minute U.S. bid to extend the treaty because of unspecified concerns, and referred to Russia’s INF-violating missiles as “a fairy tale.” In light of the INF suspension, his words cast a heavy shadow of doubt over the future of this pillar of the international arms control regime.

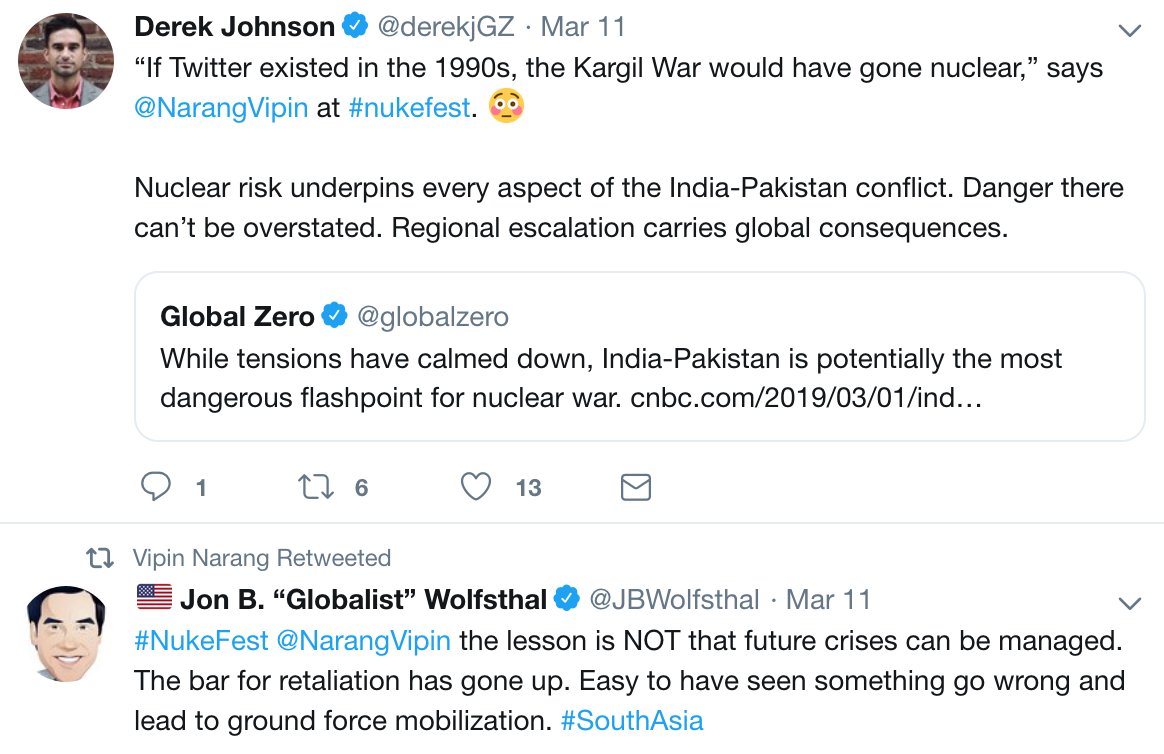

4. Twitter is (still) a force to be reckoned with. The world at large has learned that a tweet from the right person can have inestimable implications for international politics, and the nuclear policy world showed that it’s keeping pace.

Narang, speaking about the recent attack in Pulwama, mentioned Twitter as a place where public pressure to respond to an attack can build and misinformation can quickly spread, making peaceful resolution of a conflict more difficult for leaders. While a major theme of the conference was the need for more, and more open, lines of communication among nuclear-armed states, social media’s effects on politics and policy, positive and negative, were a common subject of discussion. (To catch up on the virtual side of the conference, check out the #NukeFest and #NukeFest2019 Twitter hashtags.)

5. There are plenty of reasons to hope. “Proliferation Prognostication: Predicting the Nuclear Future,” a Tuesday morning panel moderated by the Center for Nonproliferation Studies’ Jeffrey Lewis, asked the audience and panelists to try their hand at predicting the future of nuclear policy. While the results betrayed relatively low expectations, particularly for the durability and appeal of treaties, the conversation and questions underlined participants’ profound awareness of the value of diplomacy in an unstable world.