Near Misses in the South China Sea Call for a New Approach

Commander of the U.S. 7th fleet Vice Admiral Phillip Sawyer told reporters in Manila on March 18 that the U.S. Navy would continue its so-called “freedom of navigation” exercises in the South China Sea despite recent near misses with Chinese ships. That’s bad news for those seriously concerned with nuclear stability.

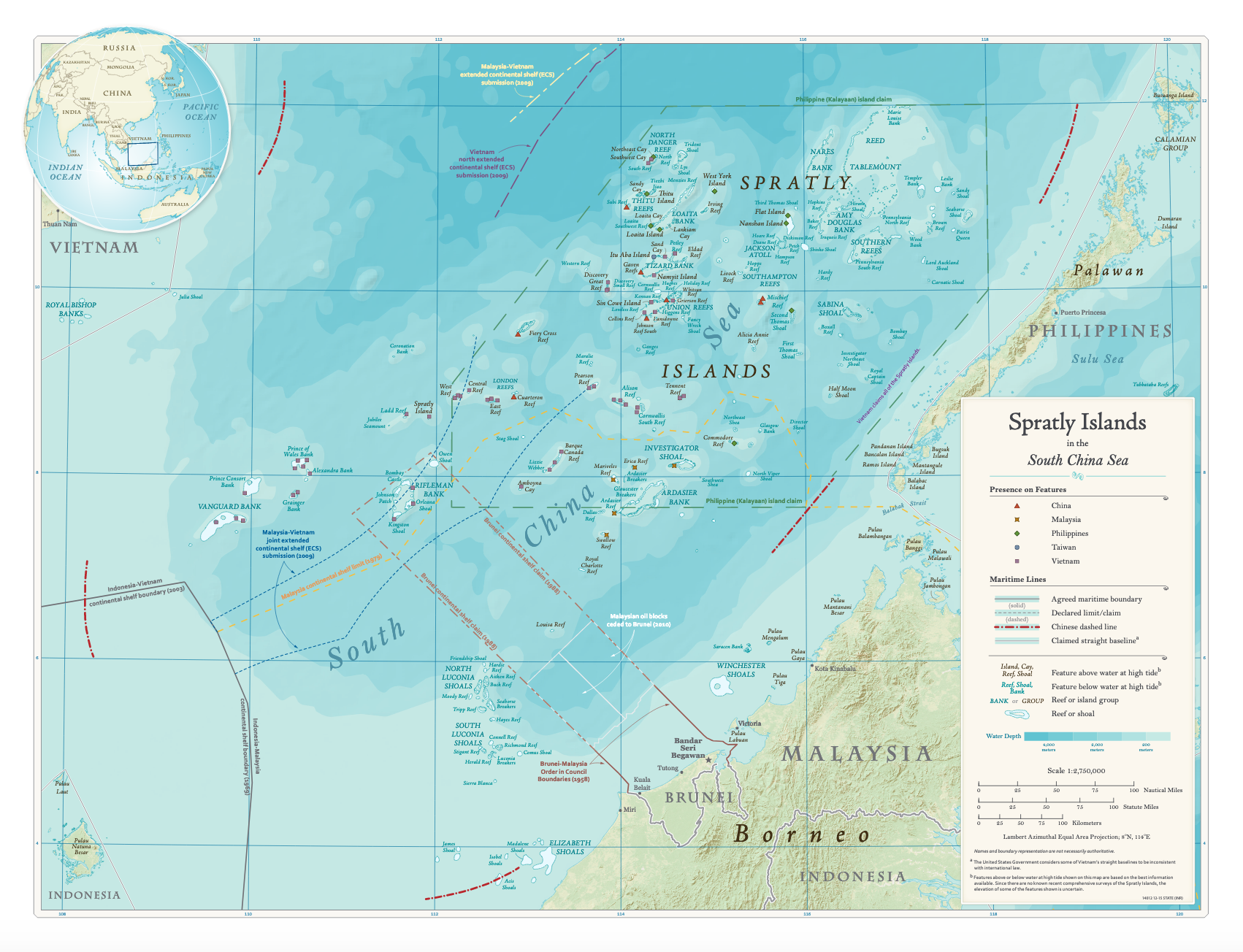

Access to the South China Sea, an area of approximately 1.4 million square miles, is highly contested by states in the region and beyond. With good reason: around one-third of all shipping passes through it; its fisheries feed much of southeast Asia, and exploration of its oil and gas reserves is only beginning.

Seven countries in the region have some claim to the area, and China, as the largest and most powerful, has taken a range of measures to secure its claims, including the extraordinary one of constructing artificial islands. The United States, mindful of the potential costs of Chinese control of the area, regularly conducts “freedom of navigation” exercises in the South China Sea, sailing within the 12 nautical-mile “territorial sea” area off the coast of islands claimed by China. The AP quoted Sawyer as saying that such patrol missions would continue in the South China Sea and elsewhere “‘until there are no excessive maritime claims throughout the world.’”

This kind of “peaceful” military operation, like the construction of artificial islands and other actions China has taken in the area, is supposed to accomplish what many seem to believe diplomacy cannot: pumping the brakes on the behavior of another nuclear-armed state through muted threats of violence.

This is dangerous. This kind of “peaceful” military operation, like the construction of artificial islands and other actions China has taken in the area, is supposed to accomplish what many seem to believe diplomacy cannot: pumping the brakes on the behavior of another nuclear-armed state through muted threats of violence. As State Department funding decreases and ambassador positions go unfilled, a military-first approach to foreign relations gains further traction.

But when you talk about “signaling” between nuclear-armed states, you’re saying the best way for two countries equipped to engage in a potentially civilization-ending nuclear conflict to communicate on difficult issues is indirectly, through heavily veiled threats.

The question of who gets to do what in the South China Sea is complicated, in part because so many states have an interest in the area. But when two nuclear-armed states resort to displays of force, even past the point where risky incidents have occurred, everybody in the world has an interest in pursuing a peaceful multilateral solution.

There’s plenty of room for that. China already has a No-First-Use policy; a U.S. No First Use declaration would reduce the risk of nuclear use across the board, and demonstrate that it’s serious about addressing the nuclear threat. And those who supported the administration’s decision to withdraw from the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty on the grounds that it did not include China would surely be supportive of an expanded approach to diplomacy. The situation is challenging, but the world cannot afford the risks inherent to the current aggressive approach.