The Military Incidents Project: Anatomy of An Air Incident

This is the second in a series of posts re-introducing Global Zero’s Military Incidents Project, begun in 2014 to track publicly-known military incidents between nuclear-armed countries. Visit the project’s homepage for additional updates and information.

In June of 2014, just a few months after Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea, a group of Russian fighter jets conducted an exercise over the Danish island of Bornholm where the Folkemødet — the “People’s Meeting” — an annual four-day political conference, was taking place. The incident only became known later, when a report from the Danish Defense Intelligence Service described it as the largest Russian military exercise over the Baltic Sea since 1991.

Since 2014, incidents involving aircraft have become so common that they are often dismissed as “routine,” and the English-language media rarely covers them. But these “air incidents” are some of the most common events tracked by the Military Incidents Project, and over half of the 993 air incidents tracked since March 2014 were intercepts conducted by NATO air police on Russian aircraft over the Baltic Sea. But each air incident presents a real risk for escalation — and that risk can be exacerbated by a range of factors. So how can we understand the factors that make an air incident potentially dangerous?

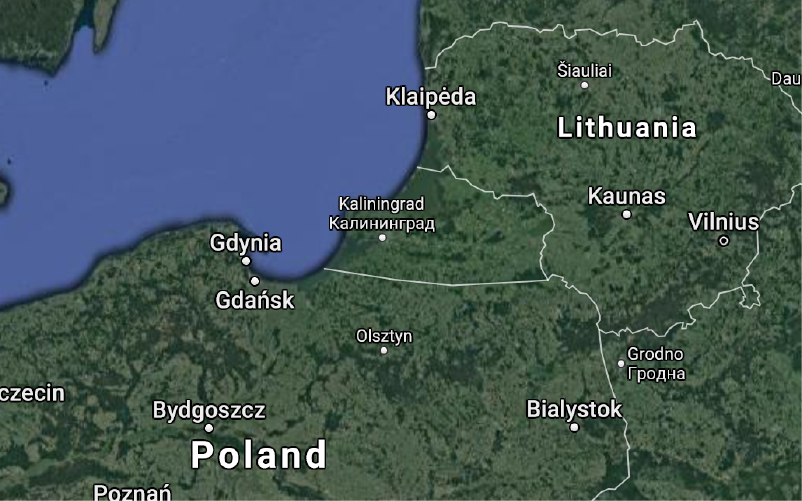

Location. In many cases, regular air incidents result from regular air operations in an area where one or more countries wants to maintain a military presence for political reasons. International airspace over the Baltic Sea is a prime example: nearly every day, NATO air police aircraft conduct intercepts of Russian military aircraft flying to and from the Russian mainland and Kaliningrad, a Russian exclave located on the Baltic Sea between Poland and Russia. Proximity to a border, or to an area formally claimed by two or more countries, can also increase the likelihood that an incident will lead to escalation.

Context. The rate and the nature of air incidents often changes in tune with world events. The U.S. announcement that it would withdraw from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in October 2018, for example, was closely followed by an uptick in the number of air incidents over the Baltic Sea, as well as a widening of the geographical area where these incidents typically occur from the southern and eastern Baltic Sea to the west and into the North Sea. Tracking them long-term shows when an individual incident is part of a trend — and when it might signal a new deterioration in relations.

Communication. Limited or unreliable means of communication among militaries and civilian leadership in a crisis can make the difference between dangerous escalation and stability. When it comes to air incidents, the two key axes of communication are among pilots and between pilots and regional air traffic control centers. Any attempt to dial down tensions and promote peace must start with ensuring that robust channels of communications exist at all levels.

Doctrine and political environment. Now more than ever, foreign policy and military doctrine are formulated and carried out with almost no public oversight. However, a country’s nuclear doctrine as well as the behavior of its leaders should be taken into account when trying to predict whether those leaders might decide to escalate a military incident to a conflict.

For example, a country with a No-First-Use policy whose nuclear forces are configured to reflect that policy (i.e. not kept ready to launch on warning) can credibly be judged less likely to use nuclear weapons first than one that explicitly maintains that it would use nuclear weapons first in certain cases. Similarly, if a government has previously issued a statement condemning a similar incident, they may be more likely to respond more aggressively to additional incidents — especially if that response would be in keeping with their past behavior.

Tracking and analyzing military incidents allows a broader audience to understand how these policies actually affect events on the ground, and to judge for themselves whether their leaders are acting in their best interest.

The next post in this series will discuss the uses and misuses of military exercises. To stay up-to-date with all project updates, visit the Military Incidents Project homepage.