The Military Incidents Project: Testing…

This is the fourth in a series of posts re-introducing Global Zero’s Military Incidents Project, begun in 2014 to track publicly-known military incidents between nuclear-armed states. Visit the project’s homepage for additional updates and information.

In October 2006, when North Korea conducted its first nuclear test, the other nuclear-armed states of the world reacted with concern — but not surprise. The New York Times characterized the news as the result of “more than two decades of diplomatic failure, spread over at least three presidencies.” North Korea’s pursuit of a nuclear weapon had been well-known for decades. Nevertheless, the first test of a nuclear capability sends a powerful and public message to the rest of the world.

Capability Tests

Previous posts in this series have detailed how ostensibly routine military operations are used for a range of signaling purposes. This is also true for tests of new equipment — or a well-timed test of an existing capability.

As countries rush to develop new capabilities and, in some cases, expand their nuclear arsenals, these tests become more frequent. North Korea offers a particularly clear-cut example of this: its tests of new missiles are greeted by a wave of anxious media coverage outside the country and accompanied by fiery rhetoric from its leaders. The implications for U.S.-North Korean relations are often unambiguous, especially when the tests have come with fiery rhetoric among leaders.

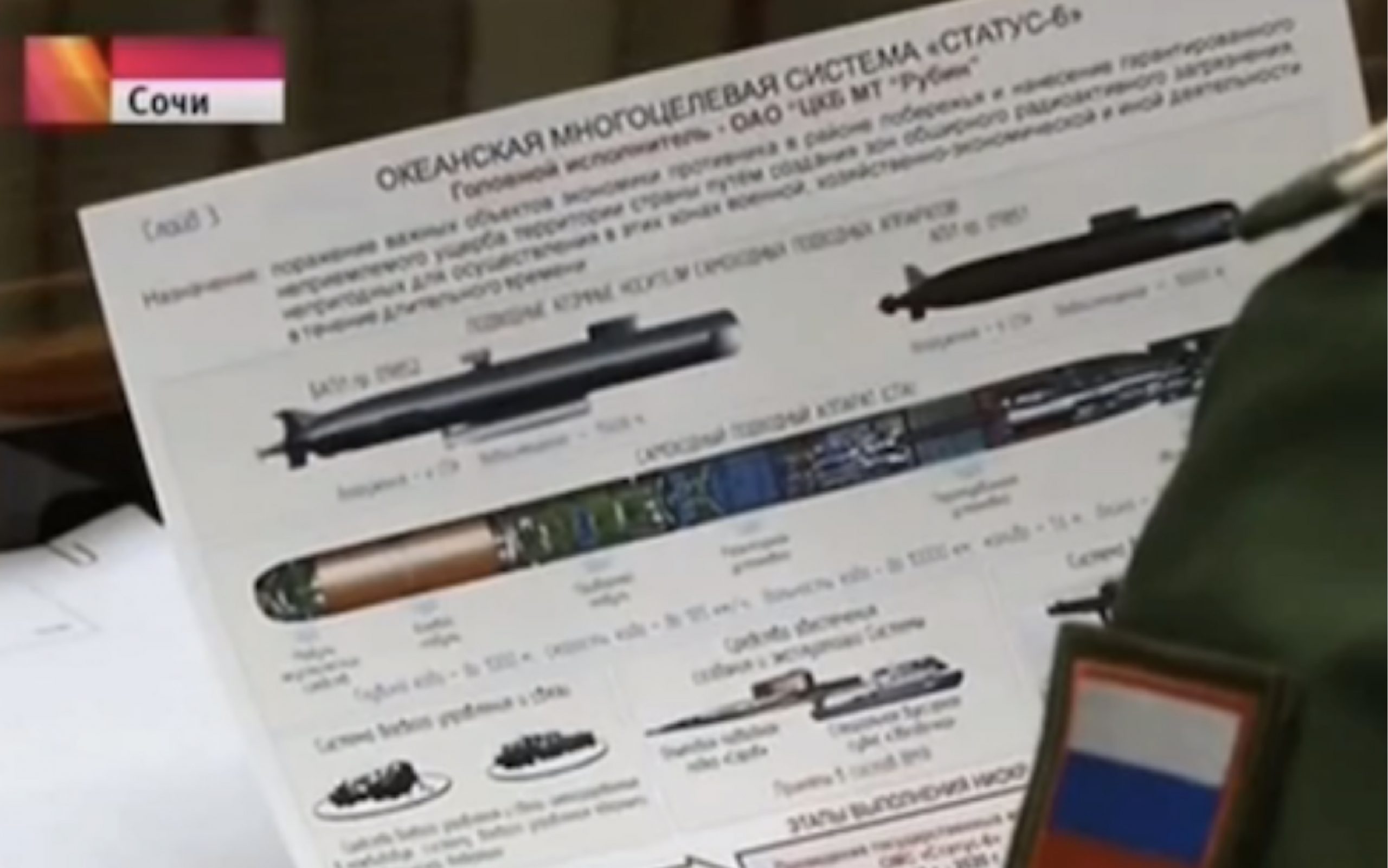

But a test can also produce ambiguity: this was the case with the program to develop Russia’s “Status-6” unmanned nuclear-powered underwater vehicle. Existence of the program was confirmed when a sheet of paper showing its key dimensions was “accidentally” revealed during a television broadcast in November 2015.

Four years later, a video that purportedly showed a test-launch of the vehicle was shown on Russian television. Though this was reportedly not its first test, the uncertainty and public anxiety generated in response to the media reception of the test clip must also be taken into account when assessing the full consequences of such a test.

As in all things, perspective is key. The U.S., for example, regularly conducts tests of its missile defense capabilities. While these tests are hardly seen as noteworthy within the U.S. itself (where many people remain blissfully unaware that the U.S. has these capabilities in the first place), they have consistently been received with alarm by Russia and North Korea. For these two countries, the U.S. emphasis on missile defense would seem to undermine the idea that a shared vulnerability to attack prevents nuclear-armed states from attacking one another.

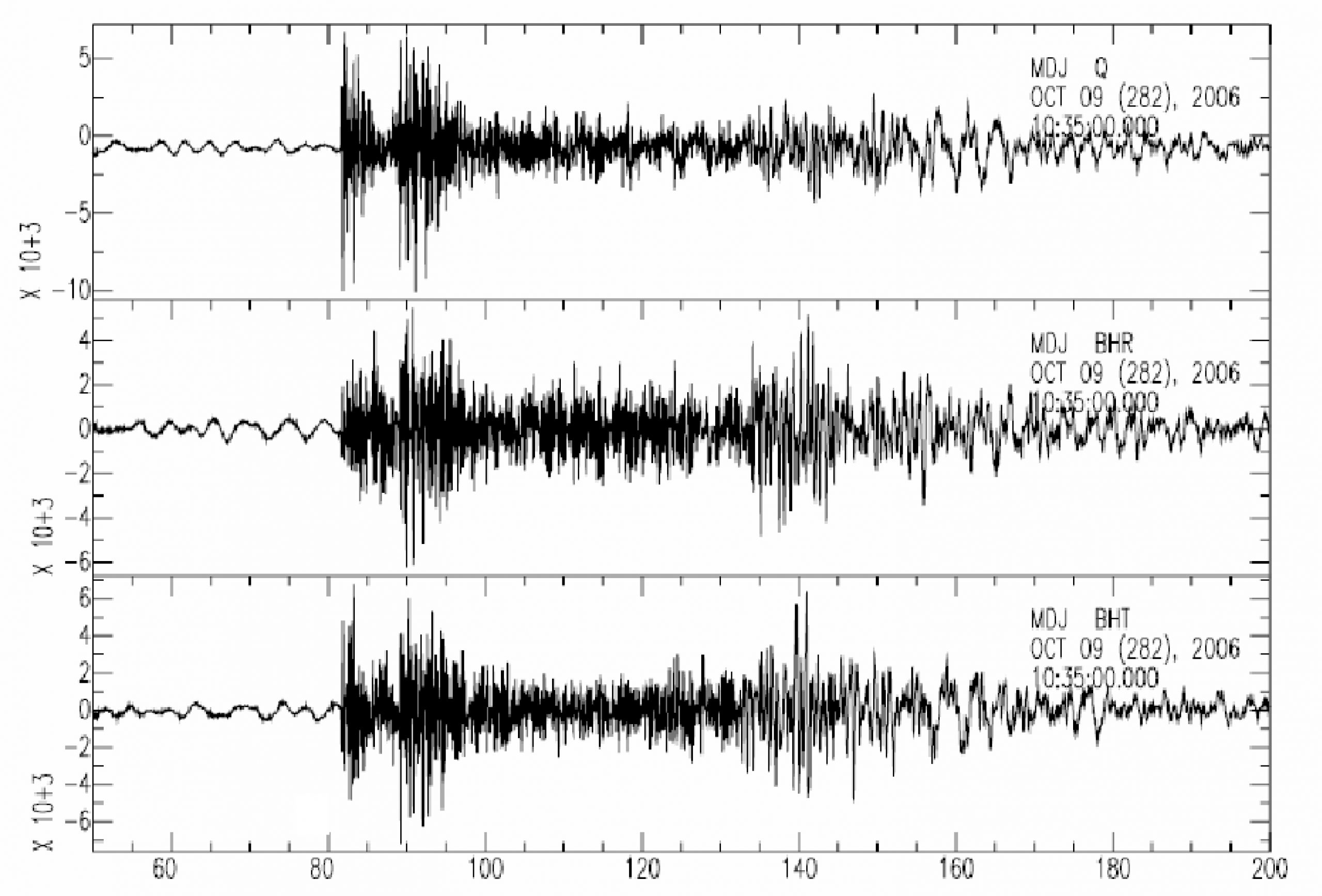

Nuclear Tests

Nuclear weapons testing was banned in 1996 with the adoption. of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. The U.S. has signed, but not ratified, the treaty.

Nevertheless, the U.S. has not tested a nuclear weapon since 1992, when it detonated its last underground nuclear test, after decades of conducting more than 1,000 atmospheric, space, underwater, and underground nuclear tests.

Unfortunately, that could change. Congressional Republicans and the Trump administration have reportedly discussed resuming nuclear testing, on the now-familiar logic that the U.S. must respond to perceived Russian aggression.

Such a test would weaken the “taboo” against using a nuclear weapon after nearly eight decades without their use in conflict. Those who support the policy agenda outlined in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review have also argued that building a lower-yield nuclear weapon would provide a more “usable” nuclear capability. Testing a nuclear weapon would go hand-in-hand with this blinkered reasoning, worsening prospects for arms control and desperately needed deescalation of this key bilateral relationship.

A test would also add to the massive amounts of nuclear material released by previous tests — a long-lasting environmental burden of the nuclear age whose full consequences have not yet been reckoned with.

Tracking tests — nuclear and otherwise — can provide insight into why this idea has proved appealing to some. But it also makes obvious the destabilizing effects of all kinds of tests, particularly when communication among states with adversarial relationships is limited. In a nuclear-armed world, a test is never just a test.

The next post in this series will introduce Global Zero’s new risk rating rubric for the Military Incidents Project. To stay up-to-date with all project updates, visit the Military Incidents Project homepage.