The Trinity Test: Dawn of the Nuclear Age

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped a nuclear weapon on Hiroshima, Japan – the first time such a catastrophic weapon was ever used in conflict. Three days later the U.S. released another on Nagasaki, devastating the city and ushering in the nuclear age. Over the next few weeks, Global Zero will explore what led to the bomb’s development, the consequences of its use, and where we’ve come since those fateful days in August. This is the third in our series “‘My God What Have We Done:’ The Legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

By 1945, the scientists of the Manhattan Project working to develop and build a nuclear weapon had made significant progress. Employees of the top-secret project developed two types of atom bombs. One used uranium and a fairly simple design, leaving scientists confident it did not need testing. The other was a more complex implosion design using plutonium. Project leaders decided this second bomb needed to be tested before it was deemed ready for use. On July 16, 1945, the first atomic bomb successfully detonated at the Trinity test site.

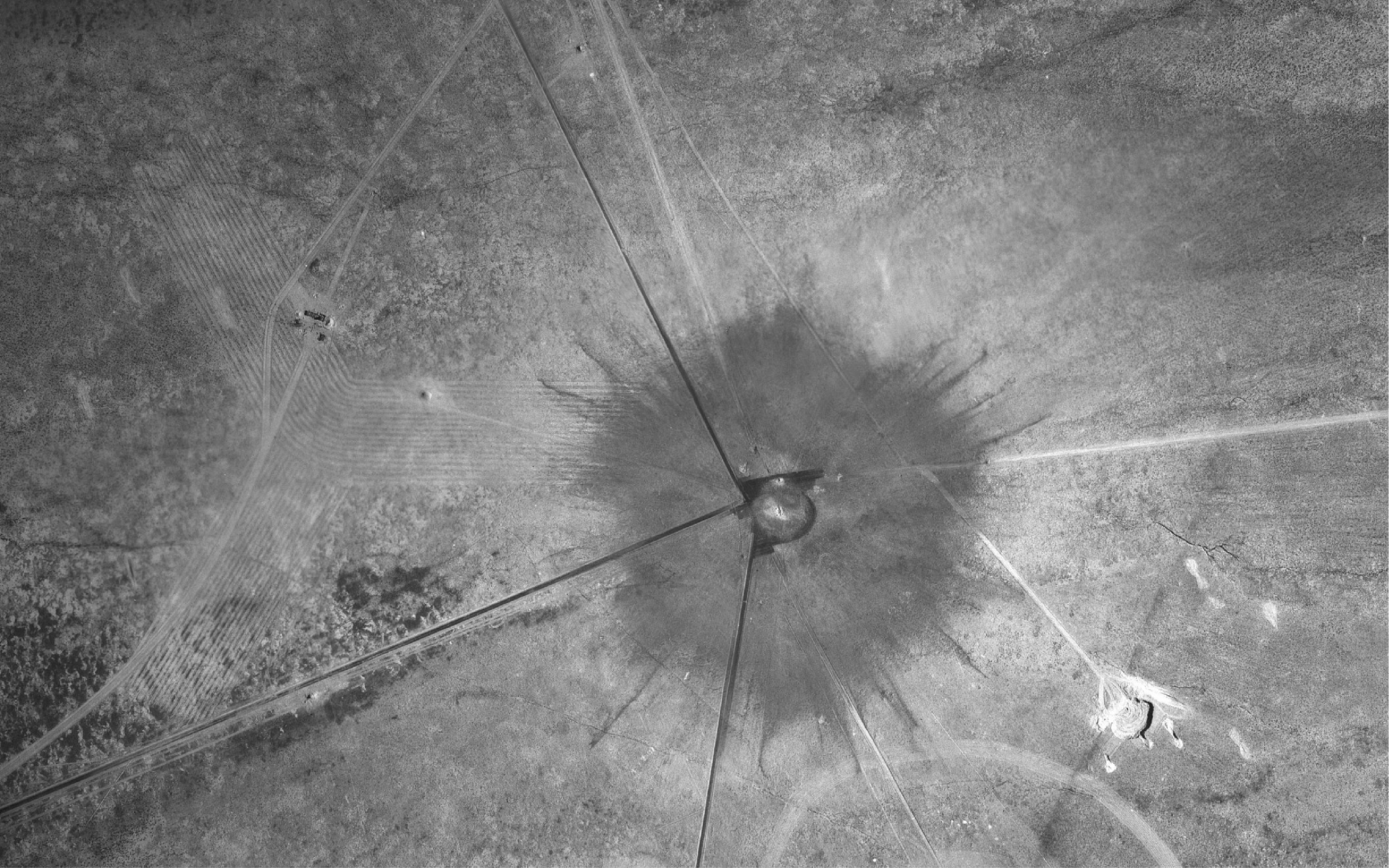

Seeking an isolated test site for both safety and secrecy, planners chose a flat desert region at a U.S. Air Force base near Alamogordo, New Mexico. While the test site was relatively barren, the nearest town was just over twenty miles away. As the test date approached, concerns grew over the possible effects of radioactive fallout on nearby towns. After receiving warnings over potential legal liabilities, Manhattan Project Director General Leslie Groves tasked the Army with setting up an offsite monitoring system and preparing evacuation plans for those in a forty-mile radius.

The morning of July 16, the test weapon – referred to as “the gadget” – sat atop a 100-foot tower. Key observers were stationed in the control shelter constructed about 6 miles from the point of explosion. Others observed from shelters similarly situated around the test site, from base camp ten miles away, from “Hill Station” twenty miles away or from the air in B-29 bombers. Thunderstorms in the area delayed the test until early morning. At 5:30 am, the plutonium bomb detonated.

Joan Hinton, a graduate student working on the Manhattan Project, described the explosion:

“It was like being at the bottom of an ocean of light. We were bathed in it from all directions. The light withdrew into the bomb as if the bomb sucked it up. Then it turned purple and blue and went up and up and up. We were still talking in whispers when the cloud reached the level where it was struck by the rising sunlight so it cleared out the natural clouds. We saw a cloud that was dark and red at the bottom and daylight at the top. Then suddenly the sound reached us. It was very sharp and rumbled and all the mountains were rumbling with it.”

The explosive force was equal to roughly 20,000 tons of TNT, far larger than the expected 7,500 tons. The flash of light was visible over 280 miles from the test site; the blast broke windows 120 miles away. Military police in nearby towns told those who saw the flash that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Radioactive green glass created from some of the dirt and debris caught in the fireball littered the test ground. Reports of public radiation exposure in the days following the test and evidence indicating high rates of infant mortality in counties downwind from the test site were largely ignored though officials did decide to forego further testing at the site in favor of a larger, more barren space. Residents of southern New Mexico are still pushing for the government to acknowledge and take responsibility for the lasting effects of the Trinity test, as detailed in a new report on the decades of health issues and deaths in the region.

Following the successful test, word was sent to U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson who relayed the news to President Truman. It was clear to everyone the most destructive weapon ever built by humankind was ready for war.

In our next post, we explore how Manhattan Project employees viewed their work on the atomic bomb both as an advancement of science and a new tool for the military.